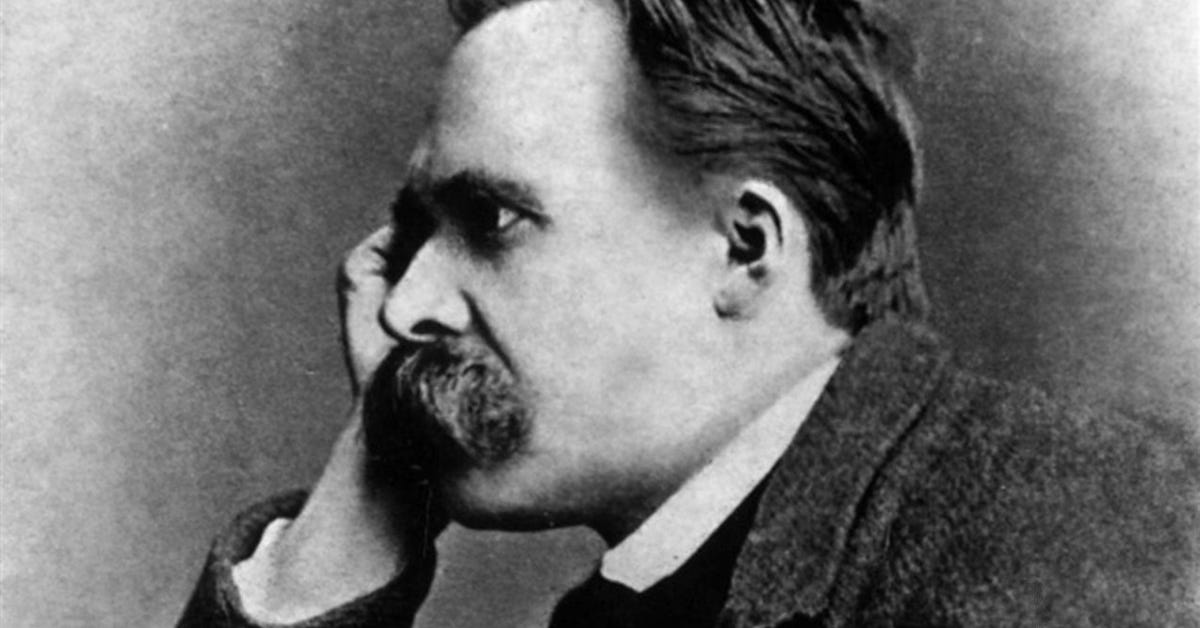

What Nietzsche Meant by “God Is Dead”

Understanding the most misunderstood sentence in modern philosophy

By Nick Holt – The Modern Enquirer

When Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that “God is dead,” he wasn’t celebrating . He was recording a cultural obituary. The phrase—perhaps the most misunderstood in modern philosophy—was not an act of blasphemy but of diagnosis.

Nietzsche was telling Europe what had already happened: that its faith, its moral compass, and its metaphysical foundation had quietly collapsed, leaving an open grave where certainty once stood.

The declaration first appears in The Gay Science (1882) and later reverberates through Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Europe was emerging from centuries of Christian dominance, but the Enlightenment’s new gods—reason, progress, and science—were proving no less dogmatic.

The Industrial Revolution had reshaped every facet of life; Darwin had displaced divine creation; and modern scholarship had begun to dissect Scripture as literature. Nietzsche saw the inevitable conclusion: if God is no longer believed in, then the moral and metaphysical structure built upon Him cannot survive.

In The Gay Science, the “madman” enters a marketplace at dawn, lantern in hand, shouting, “I seek God!” The crowd laughs. The madman announces that “God is dead. And we have killed him.” But his tone isn’t triumphant. It’s despairing.

Humanity, he says, has “wiped away the horizon” and “unchained the earth from its sun.” The metaphor is astronomical: our moral world has lost its centre of gravity.

Nietzsche’s statement isn’t so much theological as it is anthropological. God, for him, represents the highest value—whatever gives meaning and order to human existence. The death of God therefore means that the highest value has lost its value.

When faith in a transcendent source of truth collapses, so too does the coherence of every system derived from it—ethics, law, beauty, reason itself.

He saw that European culture was drifting into a vacuum. The Christian worldview had structured not only belief but also logic, art, and morality. Remove it, and what remains is not freedom but vertigo.

“What did we do when we unchained this earth from its sun?” the madman asks.

The question is both scientific and spiritual: without an absolute reference point, how do we orient ourselves?

Nietzsche observed that modernity’s newfound confidence in science and rationality had not produced new meaning but had eroded the old without replacing it. He was among the first to foresee a crisis of nihilism—a world in which all values appear baseless and all purposes arbitrary.

For Nietzsche, it’s a warning against complacency. He rejected the idea that humanity could simply continue to live on the moral capital of Christianity after rejecting its metaphysical foundation. To believe that one can discard belief yet keep its ethics is, for Nietzsche, a delusion.

“When one gives up the Christian faith,” he wrote, “one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet.”

But it is also an invitation to creation. The death of God leaves a void, but Nietzsche’s philosophy is not a call to despair. It is a summons to become what one is—to create meaning through strength, imagination, and will. His idea of the Übermensch (“Overman”) embodies this: a figure who invents new values in the absence of divine authority.

“God is dead” is not a victory cry of atheism. Nietzsche had little patience for the smug materialists of his day who thought the death of God was cause for celebration. To him, their “enlightened” optimism was simply Christianity in disguise—retaining its moral assumptions without its theology.

Nor is it a call to moral anarchy. Nietzsche didn’t argue that all values are equal or meaningless. He argued that we must confront the loss of objective grounding and take responsibility for creating new hierarchies of value.

It is not nihilism itself, but its exposure. The death of God reveals nihilism—the sense that life lacks purpose—but Nietzsche’s project was to overcome it, to forge life-affirming values rooted in human potential rather than divine command.

Nietzsche foresaw that the vacuum left by God’s death would be filled by substitutes: nationalism, ideology, consumerism, and the worship of progress. In the absence of transcendence, people would deify politics, technology, and the state.

He predicted, decades before the totalitarian century, that Europe’s coming catastrophes would be driven by the search for meaning after faith’s collapse.

“The desert grows,” he warned, “and woe to him who hides deserts within.”

His insight remains prescient. The modern West continues to live amid the ruins of metaphysics, clutching the moral vocabulary of Christianity while denying its grammar. We still speak of human rights, dignity, and equality, but we rarely ask why these should hold if there is no transcendent order guaranteeing them.

In Nietzsche’s terms, the corpse of God continues to animate our culture.

Nietzsche’s hope—if he had one—was that the individual could rise above this twilight. The Übermensch is not a tyrant but a creator: one who transforms the void into a canvas. He lives by amor fati, the love of fate, embracing existence without appeal to another world. Such a being does not mourn the death of God but fulfils the creative task it imposes: to become the author of one’s own values.

Yet Nietzsche himself was haunted by the implications of his revelation. The death of God freed humanity from illusion but also from shelter. His philosophy ends not with certainty but with risk—the risk that in becoming gods ourselves, we may prove to be unworthy of the role.

“God is dead” is not a slogan; it is an epitaph for an era. Nietzsche’s genius was to see that disbelief, far from being a liberation, is a burden: once we destroy the transcendent, we inherit its responsibilities. The question that follows his diagnosis is one we have yet to answer—whether we can bear the weight of meaning we once laid upon the heavens.

The death of God was never about theology. It was about truth, courage, and the terrifying freedom of a species that has outlived its faith.

I always feel sorry for Nietzsche… For without God, there is no hope. Though he has identified the illness… He lacks the wisdom to see the cure.