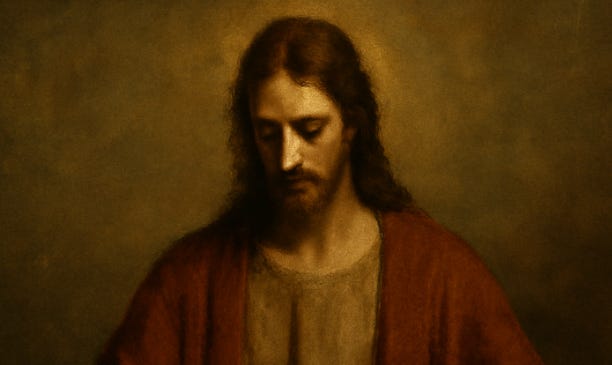

The Sexuality of Jesus

Desire, restraint, and the sacred mystery of God made flesh

Few names command as much reverence, dispute, and enduring intrigue as Jesus. For billions, He is not merely a prophet, but God incarnate—eternity in human form. But belief in the Incarnation is not upheld by mysticism alone.

It rests on a claim more radical than myth: that God entered history as a man. Not in symbol, but in flesh and blood—a body that walked, wept, embraced and bled.

And yet, across centuries of sermons, libraries of theology, and endless portrayals of Christ in art and film, one question remains largely unasked: what did Jesus know of human sexuality?

To ask this is not to defile the sacred. It is to honour it. A theology that proclaims the Incarnation mustn’t flinch from its implications. If Jesus was fully human, then He did not float through life as a disembodied moralist.

He inhabited the full condition of humanity—its hungers, its solitude, its longing to love and be loved. That includes the most elemental dimension of human experience: the erotic.

Not eroticism in the crude, contemporary sense, but eros in its classical meaning—relational energy, the magnetic pull toward union, the desire to transcend oneself in another.

The Gospels do not chronicle this explicitly, but their silences are not denials. They are invitations to reflect on a man who lived among us without retreating from the body.

Jesus never married. He fathered no children. He spoke of eunuchs who choose celibacy “for the sake of the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 19:12). In His culture, where marriage was virtually compulsory, this was not abstinence—it was revolution.

His choice to remain single was not a rejection of love but a radical redefinition of it. He did not suppress eros; He transfigured it.

Christ embodied agape—the self-giving love that finds its highest expression not in possession but in sacrifice. His celibacy was not the absence of desire, but its consecration.

In Him, restraint was not repression; it was reverence. He held the body as sacred, not sinful. The sexual impulse was not cast out, but lifted up—redeemed through discipline, not denial.

This understanding deepens when we consider His relationships. The Gospels speak of the “disciple whom Jesus loved.” He wept at the death of Lazarus. He drew near to the outcasts, the lepers, the prostitutes—not with distance, but with compassion.

He laid hands on the unclean and let tears fall in public. There was intimacy in Him—not erotic conduct, but a lived eros of presence, tenderness, and relational depth.

There is no reason to believe that Christ, in His humanity, was exempt from the ache of desire. To claim otherwise is to render His incarnation incomplete. Scripture tells us He was “tempted in every way, just as we are—yet without sin” (Hebrews 4:15).

Temptation is meaningless without sensation. The divine restraint of Jesus was not robotic; it was willed. And that will was rooted not in contempt for the body, but in its holy purpose.

The woman caught in adultery (John 8) stands as a moment of sublime grace. When others sought to stone her, Jesus knelt beside her. “Neither do I condemn you,” He said. “Go and sin no more.” This was not a sentimental reprieve.

It was the restoration of dignity. Jesus saw through the moralism of the mob and into the sacred mess of human longing. He did not deny sin, but He refused to conflate sexuality with shame.

Modern critics, especially secular scholars, often challenge the divine claims of Christ. Figures like John Dominic Crossan argue the Gospels were theological propaganda, composed decades after Jesus’ death to bolster imperial competition with Caesar.

But historical skepticism does not erase the fact that Jesus' own words and conduct pointed unambiguously toward divinity. He forgave sins. He redefined the Law. He referred to Himself as “I AM.”

C.S. Lewis articulated the dilemma bluntly: Jesus is either who He said He was—or He is mad or worse, insane. But there’s a second dilemma, less explored: if He is divine, then He is also the most complete vision of what it means to be human. His body, His longing, His restraint, His suffering—none of it can be bypassed in favour of a disembodied ideal.

The theology of the body is not incidental to His mission. Paul reminds us, “Your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit” (1 Corinthians 6:19). Jesus affirmed this with His life. He did not flee from flesh; He entered it.

He touched the untouchable. He sweat blood in Gethsemane. He gave His back to scourging. And at Calvary, He offered His body—not symbolically, but physically—as a ransom for mankind.

The crucifixion is the consummation of divine eros: the total self-giving of love. It is sexuality reimagined as sacrifice, not because sex is unclean, but because self-offering is the highest form of love. Jesus' celibacy, viewed in this light, was not a denial of the erotic but its apotheosis. The flame burned, but it was never consumed.

To reflect on the sexuality of Jesus is not to indulge curiosity. It is to deepen reverence. It reminds us that our own bodies—frail, longing, conflicted—are not obstacles to holiness but vessels of it.

His life teaches that love, in its truest form, does not begin with possession. It begins with presence, continues in restraint, and culminates in sacrifice.

We will never know the full mystery of Jesus’ inner life. But we know this: He loved. He desired. And He gave Himself entirely.

To contemplate His celibacy is not to question His humanity. It is to understand, perhaps for the first time, just how fully He shared it.

by Nick Holt