Don't let radicals like Lidia Thorpe strip us of compassion for suffering Aboriginal Australians

There are a lot of Aboriginal people who have misery and sorrows because of the impact the First Fleet caused

On January 26, 1788 the British flag was erected on Australian soil. The First Fleet reached its final destination.

One year earlier, more than one thousand convicts, civil officers, crew members and marines had departed England, destined for a new land.

It was the land Captain James Cook discovered a decade earlier.

There was no flag, no monarchy, and no gunpowder – just an ancient people who called it home.

For more than 40,000 years, Indigenous Australians had forged a spiritual relationship with the land we now call Australia.

They had cared for the land, and in turn the land provided them with shelter, water and food, and spirituality. The kind of spirituality that Europeans can’t understand. It’s not a superior spirituality; it’s simply one

They never damaged the land or overused it.

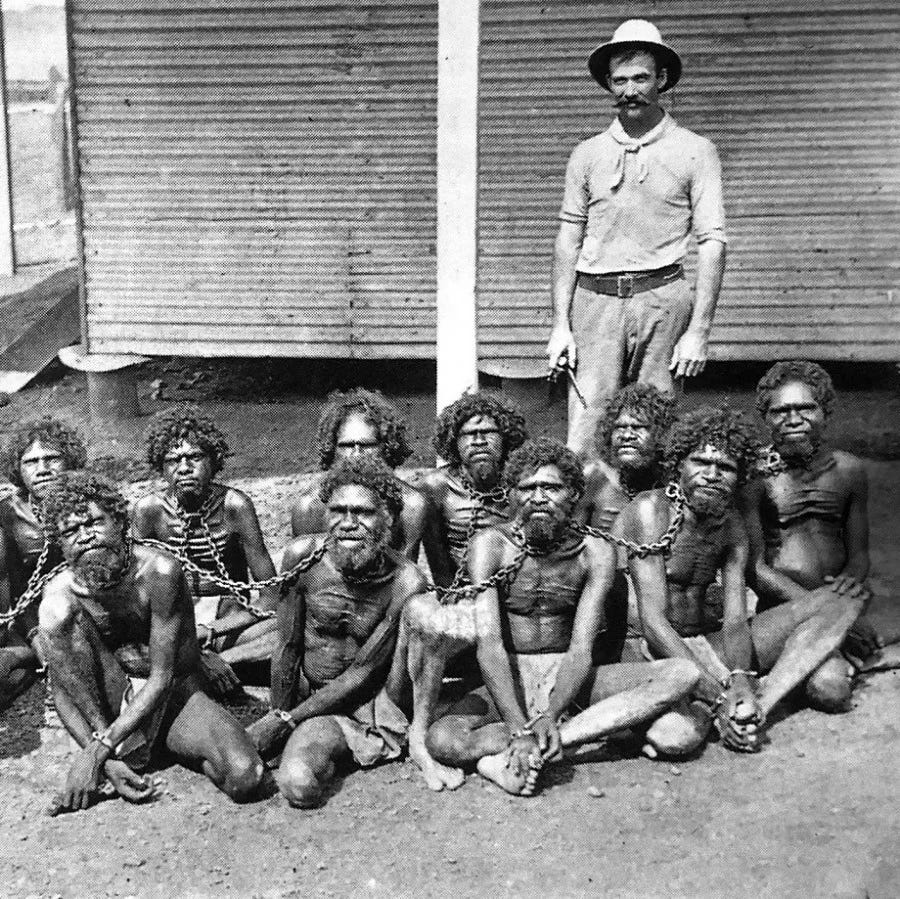

When the British exercised their claim to sovereignty over the land, the consequences were catastrophic for the First Peoples.

The British colonisers committed a wide range of atrocities against the Indigenous peoples. They removed children from their families, forced labor, massacres, and the spread of disease.

The British government also implemented policies of forced assimilation, which aimed to assimilate Indigenous peoples into British culture, and often involved suppressing Indigenous languages and customs.

When you remove a language from a people, the consequences are catastrophic:

Cultural Loss: A language is often closely tied to a culture and its traditions. When a language is removed, it can lead to the loss of cultural knowledge, customs, and practices.

Loss of Identity: A language is often an important aspect of a person's identity. When a language is removed, it can lead to a loss of self-esteem and a sense of displacement.

Loss of Community: A language is often a means of communication within a community. When a language is removed, it can lead to the fragmentation of a community, and make it difficult for people to connect with each other.

Loss of History: A language is often a repository of a people's history, stories and knowledge. When a language is removed, it can lead to the loss of historical knowledge and understanding of the past.

Loss of economic opportunity: A language is often a means of communication in business, education and other fields. When a language is removed, it can lead to limited economic opportunities.

Loss of cognitive development: Research has shown that being bilingual or multilingual can have cognitive benefits, such as better problem-solving skills and better memory. When a language is removed, it can also result in negative impacts on cognitive development.

These effects are not only felt by the people for whom the language is being removed, but also by future generations. In the decade that followed the arrival of the First Fleet, it is estimated that the Indigenous population was reduced by 90 per cent.

More than two centuries later, Aboriginal communities continue to be haunted by the ghosts of January 26, with some saying the past and present are inextricable.

Each year, the noise increases as pressure grows on the Australian Federal Government to change the date of its national holiday.

For some, there is nothing good about January 26.

“It’s actually a day for us to sit back, reflect and remember that Australia has a black history,” Brisbane’s Murri Ministry co-ordinator Ravina Waldren said.

“I know it’s a day of celebration for some, but for Aboriginal people it’s a day of mourning.”

Ms Waldren is among an increasing percentage of people who see Australia Day as an unnecessary provocation of a deeper, systemic problem.

Anthony Dillon is an Indigenous academic at Australian Catholic University who sees the situation from a different light.

“On January 26 the news is dominated by images of the protesters, protesting against Australia Day, and it’s certainly attracted a lot of interest,” Mr Dillon said.

“Why is it that for other issues such as poverty, violence, child abuse, sickness and filthy living conditions we don’t see anywhere near the same amount of interest or outrage?”

Mr Dillon questions the intentions of some protesters, and has little faith in the lasting efficacy of a date change.

“They say that it’s appalling that Australia Day is celebrated on January 26 and they feel so strongly about it that they’ve got to protest, yet, we don’t see the same outrage for other, what I would consider, more serious issues,” he said.

The complex relationship between white Australia and its Indigenous people makes the notion of Australia Day an abstract one at best. Will there ever be an agreement on a public holiday? Does the date need to be on the 26th? I believe this has nothing to do with Australia day.

The loudest critics like like Lydia Thorpe are radicals who are not interested in solving deep-rooted problems in remote aboriginal communities. They are only interested in themselves. The louder they shout, the more divisive they act, the harder white Australia pushes back. Perhaps rightly so.

The downside of this is the lack of sensitivity in the pursuit of guarding what we feel is rightful ours — a public holiday. Yes, the British invaded the aboriginals a long time ago, but the pain and suffering remains on living faces; in living house holds; and through living tears.

David Miller, a Queensland representative on the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Catholic Council, who has been a member of Murri Ministry for 24 years, is aware of the complexity of the debate.

“There are a lot of Aboriginal people who have misery and sorrows because of the impact the First Fleet caused,” Mr Miller said.

“It’s very hard for me to put it into words. What’s the best solution for this? Every time I think I’ve got a clear point in my mind, I think of something else, which disrupts that.

“It certainly isn’t simple.”